Telling Tails

GHOST OF CHRISTMAS PAST

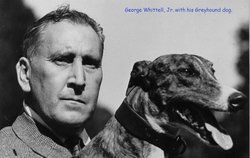

If you’ve visited animal shelters between here and the SF Bay Area, you may have noticed the name George Whittell on a building. It’s on the SPCA’s Education Center, in fact. The made for Hollywood story behind this would be a perfect vehicle for Bradley Cooper or Gary Oldman.

George Whittell Jr. died in a Redwood City hospital at the age of 87 in 1969. He left three quarters of his $40 million estate to the National Audubon Society, the Defenders of Wildlife and a number of animal hospital and pet cemeteries. Of the remainder, $6 million was bequeathed to the Society of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals to “relieve the suffering and pain of animals.” The problem was that no such organization with that exact name existed.

Naturally, the ambiguously worded will created a field day for animal groups. More than 50 staked claim to the $6 million remainder, some with stronger cases than others. The humane society located near Mr. Whittell’s Woodside estate had a good case, as did the San Francisco SPCA, since he owned property there and belonged to many social organizations. He purchased several acres on the eastern shore of Lake Tahoe and may have had landholdings in Carmel.

(As a New Year’s resolution, you might review your own estate plans to ensure your wishes are honored and not left to courts to figure out).

In the end, Mr. Whittell’s $6 million wasn’t divided among all 50 groups, but among many including the SPCA for Monterey County. This is why the wooden two-story education building on our campus bears his name.

The controversy that took place after George’s death was mild compared to the events of his life. He collected exotic animals, classic automobiles and boats, and indulged in marriages and liaisons with interesting women. Poker games at his Tahoe lodge included Ty Cobb (baseball’s original bad boy) and Howard Hughes.

His parents amassed their financial empire through real estate and railroads. One of his immigrant grandfathers shrewdly exploited the Gold Rush opportunities while the other opened a bank in San Francisco which specialized in providing loans to local merchants, and he helped found the SF Water Company, precursor to PG&E.

In 1903, George’s parents arranged a marriage for their 21-year-old son to the daughter of a prominent San Francisco couple. George eloped with a chorus girl instead and shocked everyone. It would become a way of life.

One of his surprising moves proved genius. In 1922, after his father died and left him roughly $30 million, he managed wisely and grew the fortune, then liquidated $50 million in early 1929, just before the stock market crash.

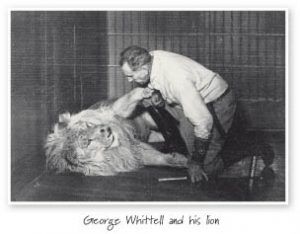

This is when life became really interesting for George. One of his ex-wives gave him a pet lion, he named Bill. The ex was out of the picture, but the lion became his closest companion, traveling with him everywhere, on leash, from San Francisco nightclubs and bars to the Tahoe shoreline.

In the 1960s, his fondness for animals grew while his tolerance for people waned and he became reclusive. His animal menagerie included his “pet” lion, an elephant named Mingo, more than 200 exotic birds, and a cheetah. He was often seen driving a Duesenberg (he owned five!) on the SF Peninsula with the cheetah riding shotgun.

When George was in his 70s, his lion fell on him and broke his leg. He never had it repaired and spent the last decade of his life wheelchair-bound.

George Whittell Jr. had many labels in life and in death. Sportsman, war hero and aviation enthusiast. Recluse, rebel and playboy.

The gift he left to animal shelters — for generations of animals, programs and visitors — was undeniably extraordinary.